It’s been quite some time since a blog post went up here. The reason for this is mainly due to my book with Packt Publishing, Serverless Design Patterns and Best Practices. Happily I can say that it’s published and I can turn my technical attention to other things.

In chapters 2 and 3, I walk through setting up serverless REST and GraphQL APIs, respectively. Both patterns use RDS as a backend datastore. One thing which is arguably overly complex with this setup is granting your Lambda functions network access to RDS. I covered the details of this in a previous post. If you follow along in that post you’ll learn how to allow inbound network access to an RDS Postgres instance on port 5432. In the Conclusion I make a note:

Also, if your Lambda function needed to speak to an external API on the public internet it would not work. This can be solved as well using NAT gateways, which will be a topic for another time.

In this post I’d like to walk through an entire setup focused around VPC networking, private/public subnets and NAT gateways. The focus will be using my previous scenario, where a Lambda function needs access to an RDS instance as well as the public internet. At the end of all this you should have a good understanding of why all of this complexity exists. There are tons of details I won’t be able to cover, but this exact scenario is quite common and one worth explaining in detail.

In my next post, I hope to cover how to create all of this complex networking via CloudFormation and Stacker, which is a great tool for managing your AWS infrastructure.

Note: I am not a networking expert! Most of the nuts and bolts of networking which I know come from setting up VPCs on AWS. Advanced networking topics get quite complex in a hurry and this is meant as an intro for developers so that they can work effectively on AWS, specifically when building serverless systems.

VPCs

What exactly is a Virtual Private Cloud from AWS and why do you care about it? In short, a VPC is a virtual network for your AWS resources which lays the foundation for any type of system you’re building. Other hosting providers by default will open your VMs or other resources to the world, meaning if you create a virtual machine all port may be open to the entire internet. Throw up some virtual machine, ssh into it, access a MySQL database, etc. When all ports are open and a machine is exposed to the public internet, development is easy. While this is very simple, it’s also very dangerous from a security perspective. With a VM or other machine exposed to public internet, you’re relying solely on credentials for protection and hoping there are no security vulnerabilities in the software which you’re running.

Note: I haven’t used other hosting providers in a long time, so this may or may not be true

for various providers. I know with Rackspace Cloud Servers this used to be the case. A Rackspace

Cloud Server would, by default, be exposed to the public internet and allow all ports to be exposed

to the outside world. It was an exercise for the developer to use something like iptables to lock

down their system tighter.

VPCs are a core component of practically any architecture you’ll build with AWS. If you don’t know the basics of VPCs, designing any system which is non-trivial will be an exercise in frustration. I highly recommend understanding VPC networking thoroughly before embarking on any type of AWS design. The good news is that the concepts in this post are enough to cover the vast majority of the cases you’ll run into.

Any new AWS account will come pre-configured with what is called a “default VPC”. Default VPCs come with a myriad of components which are required to make any VPC useful. You may read all about your Default VPC here.

If you are working with a brand new AWS account and launch an EC2 instance, it’s deployed within your default VPC. Many people who are new to AWS have no idea this is happening. Later, when deploying other resources which need a VPC, such as an RDS instance, they will again use the default VPC, which is natural. This comes in handy, since you can quickly get up and running. However, when it’s time to deploy something for real, you can get into trouble. For example, it’s a bad idea to setup a production system using your default VPC, simply for the fact that any other resource you deployed would go into the same VPC and possibly interfere with your production system. If you need to make changes to your Default VPC to support your production system, you’ll be affecting any other resource from now and into the future, including one-off EC2 instances which you may want to simply play around with.

OK, so that still doesn’t explain what a VPC is. A VPC is a virtual network which will allocate private IP address for resources deployed in it, among other things. If you’ve deployed an EC2 instance and noticed that they usually come with both a public and private IP address, it’s the VPC which is determining the private IP address. You can configure resources in a VPC to have public IP addresses as well. There are several advantages to using VPCs. The most important for this discussion are:

- Inter-VPC traffic can be routed on the private address space. Because traffic doesn’t travel across the public Internet it’s faster, more secure, and free.

- You may deploy resources in a VPC such that they are completely isolated from the public Internet. This is good for security reasons.

A VPC requires a range of IP address from which it will allocate IPs to any system deployed within

it. This range is configured via a a network CIDR, when you create your VPC. With a CIDR of

10.0.0.0/16 any system deployed in the

VPC will get an IP address in the range of 10.0.0.1 to 10.0.255.255. That equates to

65,534 unique IP4 addresses, which is a lot of AWS resources. Since you define this CIDR, you can

adjust it to fit your needs. For this post, I’ll use an example VPC with a CIDR of 10.0.0.0/16

VPCs span Availability Zones and are defined in a single Region.

When you create a VPC, you will be deploying it to a single geographical AWS Region

(i.e., us-west-2, us-east-1, etc.) Your VPCs will, by default, span all of the Availability

Zones within the region which it’s deployed.

This is important to keep in mind as we

discuss subnets, high availability an general architecture with AWS VPCs. Availability Zones

themselves are stand-alone physical systems in a given geographical region which are networked together.

They are designed such that if one AZ goes down, other AZs in the same geographical region will not

be affected. That is the promise from AWS, at least. 😁

With that in mind, any production-level system should be deployed to more than one AZ. More about this later.

Subnets, public vs. private

Within a VPC, you may define sub-regions of the network. These are subnets. Subnets also use CIDRs

to define the range of IP addresses which they will use to when something new is deployed within

them. Using the example from above, a VPC with a CIDR of 10.0.0.0/16 would need subnets which have

the form:

10.0.1.0/2410.0.2.0/2410.0.8.0/22

These are just examples…there are many may more examples. The mask at the end of a CIDR

(i.e., /8, /16, /22, 24) determines the range of your

subnet’s IP addresses and ultimately how many resources may fit into a subnet. CIDRs are really

just bit math, which I’ll skip.

There are two flavors of subnets, private and public. There isn’t any thing special about the IP range and public vs. private…it’s entirely up to you to configure these. So, what exactly are the differences? This definition come straight from the AWS docs about VPCs and Subnets.

If a subnet’s traffic is routed to an internet gateway, the subnet is known as a public subnet.

If a subnet doesn’t have a route to the internet gateway, the subnet is known as a private subnet.

Let’s drill into that.

Public subnet routing

A public subnet routes public outbound traffic through an

Internet Gateway,

which is a system

that AWS manages for you. Any traffic with a destination of 10.0.0.0/16 will be routed

locally, using VPC-internal routing. For traffic with any other destination, routing will go

through the Internet Gateway. This routing is transparent to you and allows your resource to contact

the public internet.

If we were to look at the Routing Table for a public subnet, it would look like this:

| Destination | Target |

|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/16 | local |

| 0.0.0.0/0 | igw-794bb61d |

One important thing to note here is that any resource in a public subnet can reach external resourced provided they have a public IP address. This is noted right alongside the docs referenced above:

If you want your instance in a public subnet to communicate with the internet over IPv4, it must have a public IPv4 address or an Elastic IP address (IPv4).

So, if you launch an EC2 instance in a public subnet, and that instance doesn’t have a public IP address, it won’t be able to communicate with the public internet.

Private subnet routing

A private subnet doesn’t route traffic through an internet gateway, which means that it cannot

connect to any external resources. It’s entirely possible for you to create a subnet which routes

10.0.0.0/16 traffic within your VPC without any problems, using the internal networking. However,

if a system on this subnet wanted to connect to the outside world, there would be no route for it

to get out.

The route table for a private subnet without network access would look like the following:

| Destination | Target |

|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/16 | local |

Just as a private subnet resource can’t get out, nothing from the outside world can get in. Worried about something hacking into your Postgres RDS instance or your Redis cluster? A best practice is to put systems like this in your private subnets. Now, you needn’t worry (as much) about someone hacking into them from the outside. Placing resources into a private subnet means that there is practically no risk of someone hacking directly into your database from the outside world. From a networking perspective, it’s impossible to connect to private subnet systems from outside your VPC.

So, given the case that we have an RDS instance on private subnets and a Lambda function which needs to communicate with it, what do we do? My previous post discusses how to set that up. But what do we do when our Lambda function needs to communicate with RDS and the public internet? That’s the whole point of this post. It took a while to get here, but the background story is necessary!

The answer is, change the route table to route outbound traffic through a NAT Gateway.

NAT Gateways

A NAT gateway is a resource managed by AWS which does Network Address Translation (NAT) for us, and also provides a public Elastic IP address. Once we have a NAT gateway for a given AZ, we need to setup our private subnets to use them. This change consists of adding an entry to our private subnet’s route table, to route any non-internal traffic through the NAT:

| Destination | Target |

|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/16 | local |

| 0.0.0.0/0 | nat-2351837b46c56b865 |

With this small change, anything in our private subnets can:

- Communicate within our VPC’s Private or public subnets resources on the local network using private IPs

- Communicate with the outside world via the NAT gateway

For example, something on this private subnet needs to talk to the host with a private IP of

10.0.1.23. Looking at the route table, we can see that it can go directly to that host since it has

a direct connection via local networking. Next, the same system needs to go out and make an API

call to github.com. Since github.com is not on the 10.0.0.0/16 network, the packets are routed to

the NAT gateway. On our behalf, the NAT will route our packets to github.com, and when GitHub

responds, it will route the response packets back to us. There are many details which make this

work which are not important for this discussion. Just know what the NAT gateway is doing for you

and you’ll be good.

Another interesting result of this change is that our Lambda functions will have a fixed inbound IP address when connected to external resources. That IP address will be the IP of our NAT gateway, which typically is an Elastic IP. This has the added benefit of giving our Lambda functions (mostly) static IPs if you even face the situation where IPs need to be white listed.

Note: I’m working on a project now where we need to talk to the Salesforce API. Every IP we connect from needs to be white listed. NAT gateways is our solution to this when talking to Salesforce via Lambda functions.

VPC and Subnet Design

With any sort of system where you care about uptime, it’s crucial to set your network up across

availability zones. Rather than deploying all of your systems into, say, us-west-2a, you would

need to deploy across AZs, including at least one more of us-west-2b or us-west-2c. Why?

Remember back when I told you that AZs are independent physical systems (buildings, I presume) that

AWS manages for you, and that if one AZ goes down, the others should still function? Well, if

you’ve deployed your entire infrastructure to us-west-2a and that AZ goes down, so to does your

entire system.

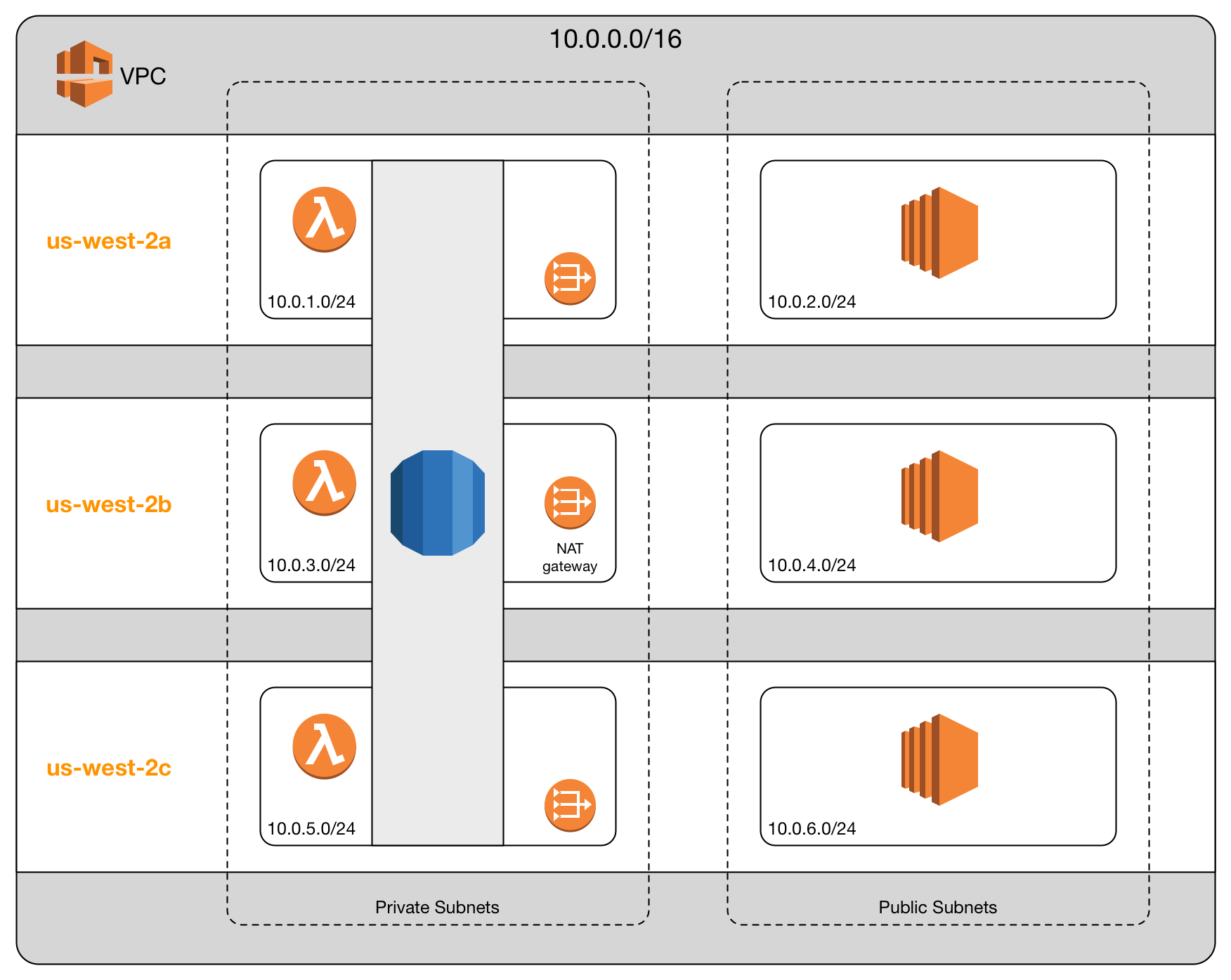

A standard practice for real system is to create public/private subnets across multiple AZs and

then deploy resources across these AZs. My nifty little diagram attempts to illustrate this. This

diagram shows a single VPC with a CIDR of 10.0.0.0/16 deployed in the Oregon region, which is

us-west-2. This VPC contains three pairs of public/private subnets, one in each of the three

availability zones.

In this scenario, a single RDS instance is deployed across all three of the private subnets. Honestly, I don’t know the details on how this is handled, but deploying RDS across three AZs ensures our database will stay up even when an AZ goes down.

Alongside RDS is a Lambda function, which is also deployed across three AZs. In the public subnet are three EC2 instances which we’ll assume are all doing the same thing. We deploy three of them to cover ourselves in the case that an AZ goes down.

In order to allow our Lambda functions outbound internet access, we need to create a NAT gateway in each AZ. That is important to remember…VPCs may span AZs, but NAT gateways do not. There is a 1-to-1 mapping with NAT gateways and availability zones, or more accurately, private subnets.

Conclusion

Phew…that’s a lot. I can promise you that if you intend to stick with AWS architecture, knowledge of VPCs is a must. What I covered above will get you a very long way, especially when dealing with serverless systems and/or a typical SaaS application.

Once armed with this knowledge, the next hurdle is learning how to exactly create and manage all of these pieces. Each piece on it’s own isn’t terribly complex, but when it’s time to create a VPC from scratch there are a lot of pieces to the puzzle, all of which must fit together properly in order for your system to work.

In my next post I’d like to cover Stacker, which is Python application which helps manage CloudFormation scripts. Stacker has several built-in “blueprints” for common systems like VPCs. Creating a new VPC from scratch isn’t for the faint of heart if you’re new to it, but Stacker can do pretty much all of the hard work.